|

|

#31

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|

#32

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|

#33

|

||||

|

||||

|

http://www.forbes.ru/forbeslife-colu...erezagruzka-74

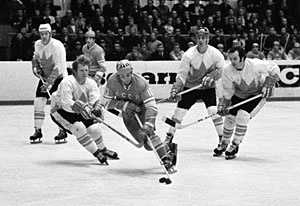

17.09.2014 04:00  фото РИА Новости Второй суперсерии с канадцами, нарастившей социальный капитал по обе стороны океана, исполняется 40 лет Однажды знаменитый голкипер Montreal Canadiens, один из главных хоккейных интеллектуалов Кен Драйден сказал: золотой век хоккея — это время, когда вам было 10 лет. В октябре 1974-го, когда в Москве проходила вторая часть суперсерии-1974 СССР — Канада (ВХА), мне было 9 лет. Я видел эти матчи, в том числе один — живьем. И помню силуэт — с аристократически прямой спиной — 46-летнего Горди Хоу, ровесника моего отца, который сидел здесь же, рядом со мной на трибуне «Лужников», а на лед выходили оба сына Хоу — Марк и Марти, 19 и 20 лет соответственно. Для скольких поколений Хоу олицетворял «золотой век», если он начинал в сезоне 1945/1946, а закончил в сезоне 1979/1980! А еще помню Бобби Халла — «Золотую ракету», человека, воплощавшего в себе одновременно пращу и стрелу, который тоже был мужчиной по нынешним спортивным понятиям возрастным, но быстрым, как сама шайба, пущенная им. В нем не было мистической пластики Валерия Харламова или баскетбольной мощи Александра Якушева, но в той суперсерии он набрал очков по системе гол плюс пас больше и того, и другого и забросил больше всех шайб — 7. Чем страшно гордился: ни один хоккеист из Северной Америки не забивал столько Владиславу Третьяку. Халл говорил о том, что исключение его из команды Канады в 1972 году за переход из НХЛ во Всемирную хоккейную ассоциацию (ВХА) за чек в миллион долларов стало самым сильным разочарованием в жизни. Но пиком карьеры он считал первый матч суперсерии-74: два гола и одна голевая передача, счет 3:3. Наши выиграли в той суперсерии, начавшейся 17 сентября 1974-го как бы ремейком событий 2 сентября 1972 года в Монреале, когда состоялся во всех смыслах исторический первый мачт СССР — Канада (НХЛ). Символическое вбрасывание от Пьера Эллиотта Трюдо в 1972-м, принесшее ему трудную победу на выборах, было повторено спустя два года. В 1974-м, несмотря на высочайший уровень показанного хоккея, по ощущениям все было не так свежо. Большинство ждало, в отличие от 1972-го, поражения канадцев. ВХА, входившая в свой третий сезон, считалась лигой, уступавшей НХЛ. Наша сборная была моложе и быстрее, а ворота защищал вошедший в пик карьеры вундеркинд Владислав Третьяк — при всем уважении к подвижному Джерри Чиверсу, он был вратарем старой школы, ближе к 1960-м, стилистически примыкавшим к эре Жака Планта. Тем не менее сборная НХЛ-1972 тоже не отличалась молодостью, да и в те времена это не считалось большим недостатком, тем более в Канаде, а в сборной Канады-74 хватало блистательных и очень разнообразных звезд. К тому же ВХА считалась лигой, исповедовавшей в большей степени атакующий хоккей, чем НХЛ. Защитник Пэт Стэплтон, звезда серии-72, играл в паре с выдающимся дефенсменом Жан-Клодом Трамбле – оба перешли из НХЛ. Центрфорвард Ральф Бэкстрем, набравший в сезоне ВХА 83 очка, игравший в одной тройке с Горди Хоу и его сыном Марком. Марк Тардифф, Серж Бернье и Режан Уль (Тардифф и Уль успели поиграть в НХЛ в Montreal Canadiens) составили тройку French selection – парафраз энхаэловской тройки Рик Мартин — Жильбер Перро – Рене Робер из Buffalo Sabres, которых называли French connection. Легенды 1972-го – Фрэнк Маховлич, которому молва приписывает случайное отвинчивание гигантской люстры в холле гостиницы «Интурист» (искал кагэбэшные жучки), и Пол Хендерсон, автор победного года, заброшенного за 34 секунды до конца первой суперсерии в ворота Третьяка. Горди Хоу, «Железный локоть», «мистер Хоккей», 3 гола, 4 голевых передачи – он уступил в общем зачете только Халлу, Якушеву, Харламову и Бэкстрему. Билл Харрис, тренер, уж точно не уступавший экспансивному коучу-72 Гарри Синдену, швырявшему стулья на лед «Лужников»: за пять лет до суперсерии-74 он играл на чемпионате мира 1969-го против сборной СССР, а затем изучал игру русских, будучи тренером сборной Швеции на олимпиаде в Саппоро. Харрис пообещал джентльменскую игру. Подвел только Рик Лей, сломавший Харламова – но этого искушения мало кому удавалось избежать: хоккейный гений, чьи движения мог декодировать только криптограф, провоцировал на одно решение проблемы – удар по ногам, а то и по голове. У Лея был предшественник в 1972-м – Бобби Кларк, но оба они выглядели вегетарианцами по сравнению с Ван Импе, в буквальном смысле едва не убившим Харламова 11 января 1976-го в матче ЦСКА с Philadelphia Flyers – после этого инцидента тренер Константин Локтев увел свою команду в раздевалку. Сборная СССР представляла собой вполне зрелый продукт смены поколений, начавшейся в конце 1960-х. Это была конструкция-прообраз сборной, которую потом будет тренировать Виктор Тихонов. То есть в некотором смысле это был переходный период от эпохи Анатолия Тарасова — Аркадия Чернышева к эпохе Виктора Тихонова — Владимира Юрзинова. Только, конечно же, Борис Кулагин по прозвищу «Мао» (за разрез глаз) тоже был целой эпохой и в этом смысле совершенно незаслуженно остался в тени Тарасова, Тихонова и даже Всеволода Боброва, с которым он работал с 1972 года. 1974-й стал для него годом испытания и триумфа: после чемпионата мира в Хельсинки, когда Боброва за острый язык отправили в отставку, он возглавил сборную СССР и взял себе в помощники Константина Локтева из ЦСКА и Владимира Юрзинова из «Динамо» (Москва). Этот триумвират приводил к победам на чемпионате мира в 1975-м и в Олимпийских играх 1976 года, но на ЧМ-1976 и ЧМ-1977 случились два прокола – серебро и бронза вместо золота. Тогда-то и наступила эра Тихонова. Но именно при Кулагине, например, заиграла великолепная тройка Хельмут Балдерис – Виктор Жлуктов – Сергей Капустин. Причем это был продукт настоящей межкомандной селекции: «Динамо» (Рига) – ЦСКА – «Крылья Советов». Тихонов получил эту тройку в готовом виде – Балдериса и Капустина просто забрал в ЦСКА… В том же 1974-м Кулагин на один год прервал скучное доминирование в чемпионатах СССР армейского клуба: свежая и амбициозная команда «Крылья Советов» стала чемпионом Союза. Поэтому в сборной, которую Кулагин выставил против Канады в 1974-м в заявленном составе было 12 человек из «Крыльев» (хотя, конечно, в результате не все вышли на лед). Кроме того, конечно же, заслуга Боброва и Кулагина – восстановление в сборной СССР еще в декабре 1972-го тройки Михайлов — Петров — Харламов – после всех не слишком удачных тарасовских экспериментов. Тройка на чемпионате мира 1973 года в Москве забросила… 33 шайбы, из них Владимир Петров – 18. Кленовый лист на льду Франкофонный канадский писатель Рош Карье стал культовым и программным (с точки зрения даже школьной литературы), а цитата из его внешне простенького рассказа «Отвратительный кленовый лист на льду» попала на 5-долларовую купюру. О чем рассказ? 1946 год, Сен-Жюстин, Квебек, 2000 жителей. Школа, церковь, каток. После молитвы мальчишки скатываются от церкви на холме к катку – на коньках и с клюшками. Каждый – каждый! – в красно-синем свитере Montreal Canadiens c номером 9 на спине. Номером Мориса «Ракеты» Ришара. Мальчик вырастает из свитера. Его мать заказывает новый. По ошибке по почте приходит свитер заклятых врагов франкофонных Canadiens – англоязычных Toronto Maple Leafs. Мать заставляет мальчишку надеть этот свитер. Его ждет обструкция друзей и тренера, а местный священник отправляет отступника просить прощения у господа. В церкви мальчик просит Бога, чтобы тот наслал моль на свитер с кленовым листом. Франкоканадская ментальность послевоенных лет. Но не только. Верность команде и ее идолам, а также верность идолов команде – мог ли Ришар играть еще где-то, кроме Canadiens?! – свойство времен original six, тех лет, когда в НХЛ играло всего шесть команд. Да, конечно, эта чисто канадская ценность была размыта хоккейным рынком к началу 1970-х. Но когда возникла новая лига – Всемирная хоккейная ассоциация — и она стала скупать игроков, и первым знаковым приобретением была покупка за дикие деньги Бобби Халла, когда она разрослась не столько по Канаде, сколько по Соединенным Штатам, это и вовсе казалось не только порчей рынка зарплат и трансферов, но разрушением основ в ментально-моральном смысле. Старая канадская хоккейная матрица рушилась на глазах – игры с Советами, проникновение другого стиля игры, потом появление первых европейцев, шведов, в НХЛ, учреждение Rebel League, бунтующей лиги – ВХА, резкий рост зарплат, размывание ценности верности команде, игроки и команды из США… Затем пошли беглецы из соцлагеря – например, Вацлав Недомански – тот самый, который был «второй проблемой СССР» после острова Даманский. Что характерно, бежал не в НХЛ, а в ВХА, в Toronto Toros. Во Всемирной хоккейной ассоциации старые звезды обрели второе дыхание и заиграли едва ли не лучше прежнего. «Золотая ракета» считал, что его партнеры по звену в Winnipeg Jets Ульф Нильссон и Андерс Хедберг, звезды шведского хоккея, образовали с ним вообще «самую интересную тройку». Даже Жак Плант – в 46-летнем возрасте, в 1975-м, вернулся на лед в Edmonton Oilers. Это все равно что в здание Института марксизма-ленинизма неожиданно вошел бы лично Карл Маркс… Так что серия СССР — Канада-74 уже не была в полной мере холодной войной на льду, битвой двух политических систем и двух хоккейных школ. ВХА самоутверждалась в конкуренции с НХЛ. Сам хоккей превращался в более конкурентный. И он стал другим, перестал быть отдельно канадским и отдельно европейским. Правда, для этого должны были закончиться 1970-е, «красная машина» — ослабить свою хватку, канадский хоккей – оказаться заселенным бесчисленными шведами, чехами, словаками (братья Штястны бежали в Канаду втроем, а потом Петер Штястны нарожал новых хоккеистов – Пола и Яна), финнами, а потом и русским, и латышами. И пережить внутренний кризис середины того десятилетия. Кризис этот был связан с тяжелым явлением, отчасти спровоцированным дурновкусием публики и примитивизацией хоккейного рынка, -- невероятной жестокостью на площадке, превратившей хоккей в бойню и предмет дискуссий в канадском парламенте. Это была болезнь перехода, реакция на прекращение автаркии североамериканского хоккея. Послевоенные поколения уступали место молодежи на десятки сантиметров выше и много килограммов тяжелее. А главное, несмотря на образцы скорости, которые задавали по эту сторону океана Бобби Халл или Иван Курнуайе, а по ту сторону – Валерий Харламов и Хельмут Балдерис или быстро гаснувшие звезды вроде Бориса Александрова, новый хоккей становился гораздо более стремительным: старые записи даже лучших матчей кажутся сегодня замедленной съемкой. Но для начала, в самой первой игре, просто сразу, на закуску, был подан один из исторических голов Валерия Харламова. По странной иронии хоккейной истории – почти полная калька его же гола в первой игре сентября 1972-го. Физику и химию его движений, которые начались еще в своей зоне, снова не смог разгадать никто из канадцев, включая вратаря Джерри Чиверса, хохмача и обладателя знаменитой маски с отмеченными на ней «швами», которые пришлось бы накладывать на лицо голкипера, будь оно незащищенным (отголоски старых споров канадских тренеров и вратарей «между собою», играть ли им в маске или нет). Собственно, Харламов много сделал для очеловечивания образа русских «комми». Валерий Борисович, басконец по матери, сын простого русского рабочего, невысокий и обаятельный, был человеческим лицом коммунизма. Вот уж кто рвал железный занавес по-настоящему без ущерба для советского патриотизма. Характерно, что, когда в 1978-м Борис Михайлов и Владислав Третьяк получили по ордену Ленина, Харламову дали только Трудового Красного Знамени (правда, во второй раз). Что-то в нем было все-таки несоветское. Наверное, он принадлежал миру… Чувство льда Хоккей -- исторический, политический, а главное – социокультурный феномен, чьи коды еще не разгаданы. Когда появилась моя книга, посвященная 40-летию суперсерии-72 «Холодная война на льду», изданная исключительно в подарочном формате, но при этом висевшая на нескольких сайтах, в том числе сайте Федерации хоккея России, на меня обрушился шквал писем и звонков с просьбой любой ценой отдать, передать, продать книгу. Наиболее пассионарные читатели просто проникали в редакцию, и я им дарил по несколько экземпляров. Это была не просто ностальгия по собственной молодости или детству, по настоящим кумирам. Читателям было важно ощущать от страниц книги запах разорванной изоленты, мышечной памятью обволакивать грани клюшки и зажмуриваться от снежной пыли после торможения на льду – как это бывало много лет тому назад. Главное – это чувство льда. Почти мистическое. При этом хоккей не стал в России, даже сегодняшней, тем, чем он был и остается в Канаде и, подозреваю (по личному опыту общения) в Швеции и отчасти в Финляндии, Чехии и Словакии (для чехов хоккей еще стал и способом ответить Советскому Союз за вторжение в августе 1968-го). Помню недавний разговор о хоккее с депутатом шведского риксдага, на досуге -- детским тренером по хоккею, при этом… женщиной под 50. Подобного рода феномен у нас все-таки отсутствует, да еще на столь высоком государственном уровне… Из того же классического рассказа о хоккейном свитере следует, что средний канадский мальчишка – в любом городке – жил в треугольнике «школа-церковь-каток», но именно каток был главным местом жизни и воспитания ценностей и чувств. Именно каток (общий и/или на заднем дворе дома) или замерзший лед озера (вариант: залива) были тем пространством, из которого рождались нация, равенство всех канадцев -- перед воротами, клюшкой и шайбой. Равенство детей итальянских эмигрантов Фила и Тони Эспозито и утонченного интеллектуала, обладавшего очевидными литературными способностями, юриста, выпускника Макгилла Кена Драйдена, уроженца далекого шахтерского поселка Бобби Кларка и франкофонного полицейского Ги Лапуана, не знавшего до той поры, пока он не попал в сборную, английского языка. Хоккей примирял французскую Канаду с английской – в этом смысле не было ничего более важного, чем суперсерии, затем Кубок Канады, Кубок вызова и начало участия настоящих мощных канадских сборных в чемпионатах мира второй половины 1970-х. Именно хоккей стал клеем нации, ее базовым социальным капиталом, и он же открыл Канаду миру. В СССР хоккей в течение примерно четверти века, отсчитывая от начала 1960-х, тоже был способом нарастить социальный капитал и одновременно социальным лифтом. Правда, несколько искаженным, потому что если на определенном этапе карьеры талант из глубинки не попадал в ЦСКА или хотя бы в одну из топовых московских команд, он не мог стать по-настоящему всесоюзной звездой. В Канаде первые лица в хоккее были иконами. У нас они становились не столько иконами, сколько героями, бойцами на передовой холодной войны, почти без права проигрыша. И в этом принципиальное отличие. Собственно, других героев не осталось, поэтому сегодняшние «патриоты» героизируют с помощью важнейшего из искусств, например, того же Валерия Харламова. …Что же до ВХА, то кончина лиги знаменовала собой конец календарных и хоккейных 1970-х: начинание бизнесменов Гарри Дэвидсона и Денниса Мерфи, не слишком хорошо отличавших хоккейную клюшку от клюшки для гольфа, расширив географию североамериканского хоккея и способствовав изменению природы игры, умерло, подарив четыре франшизы НХЛ и завещав хоккейному миру масштабнейшую звезду, тогда еще совсем юного Уэйна Гретцки, автора классической фразы «Ненавижу посредственность!» Начиналась новая эпоха, возможно, не менее яркая. Но не провоцирующая такую щемящую ностальгию. Точнее, чувство льда. Последний раз редактировалось Chugunka; 12.06.2021 в 05:45. |

|

#34

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|

#35

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

#36

|

||||

|

||||

|

http://www.hhof.com/htmlspotlight/sp...eamCan72.shtml

27 NOVEMBER 2012 Team Canada head coach Harry Sinden behind the bench during the 1972 Summit Series. Team Canada head coach Harry Sinden behind the bench during the 1972 Summit Series. (Photo by Frank Prazak/Hockey Hall of Fame) Prior to 1972, international hockey tournaments refused to allow professionals to compete, so while Canada was sending senior teams or teams comprised of university players, they were playing against Soviet players who were being paid to be in the military but, in fact, were playing hockey year-round. The Canadian hockey community tagged them as 'sham-ateurs.' In fact, Canada dropped out of international competition in 1970 because the country was denied the use of the nation's best players. Then, in 1972, after much negotiation and for the first time ever, Canada's best hockey players were given the opportunity to face the best from the Soviet Union in a tournament. Alan Eagleson, the president of the National Hockey League Players' Association, was responsible for putting the tournament together in cooperation with Hockey Canada. In April 1972, he announced that an eight-game tournament -- four games in Canada and four in the Soviet Union -- would take place in September of that year, and would pit the best against the best.  Team Canada's Red-White game during training camp at Maple Leaf Gardens leading up to the 1972 Summit Series against the Soviet Union.  Team Canada's Red-White game during training camp at Maple Leaf Gardens leading up to the 1972 Summit Series against the Soviet Union. (Photo by Graphic Artists/Hockey Hall of Fame) Harry Sinden left hockey in 1970 when the Boston Bruins refused to give him a raise, but when the company he worked for went bankrupt, he made it known that he would like to return to hockey, and in June 1972, Eagleson hired Sinden to be coach and general manager of Team Canada in the tournament that would come to be known as the Summit Series. Sinden suggested John Ferguson as a playing-coach, but after being out of hockey for a year, Ferguson stated that he did not want to play and subsequently took on the role of assistant coach. Eagleson, Sinden and Ferguson compiled a list of 35 players that they would invite to camp in Toronto. On July 12, 1972, they announced their roster. In goal, they had Gerry Cheevers, Ken Dryden and Tony Esposito. On defence, they selected Don Awrey, Gary Bergman, Jocelyn Guevremont, Jacques Laperriere, Guy Lapointe, Bobby Orr, Brad Park, Serge Savard, Rod Seiling, Pat Stapleton, J.C. Tremblay and Bill White. The players chosen at forward were Red Berenson, Wayne Cashman, Bobby Clarke, Yvan Cournoyer, Marcel Dionne, Ron Ellis, Phil Esposito, Rod Gilbert, Bill Goldsworthy, Vic Hadfield, Paul Henderson, Bobby Hull, Dennis Hull, Frank Mahovlich, Peter Mahovlich, Richard Martin, Jean-Paul Parise, Jean Ratelle, Mickey Redmond and Derek Sanderson.  Canada's Frank Mahovlich with a scoring chance against Vladislav Tretiak of the Soviet Union during Game 1 action of the 1972 Summit Series at The Forum in Montreal on September 2, 1972. Canada's Frank Mahovlich with a scoring chance against Vladislav Tretiak of the Soviet Union during Game 1 action of the 1972 Summit Series at The Forum in Montreal on September 2, 1972. (Photo by Frank Prazak/Hockey Hall of Fame) From the outset, Clarence Campbell ruled that no NHL players would be permitted to play in the tournament. That summer, Eagleson, with help from Bill Wirtz, the owner of the Chicago Black Hawks, finally convinced Campbell that NHL players could compete in the series, but only if they had a signed contract with their National Hockey League team. And at the same time, the NHL was getting into a long, protracted battle with the World Hockey Association, which was just then starting to take runs at signing NHL players. To protect the NHL and to strike back at the WHA, Campbell insisted that only National Hockey League players would be permitted to play in the series. Campbell ruled that the WHA had not entered into a relationship with the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association, which arranged all international games for Canada. Because the NHL had an existing agreement with the CAHA, only players who had signed a standard NHL contract would be allowed to participate in the series. This ruling eliminated Gerry Cheevers, Bobby Hull, Derek Sanderson and J.C. Tremblay, who had already signed with teams in the WHA. Jacques Laperriere had to decline the original invitation due to the health of his pregnant wife and Bobby Orr announced that knee surgery eliminated him from competing. Replacing those players were Ed Johnston of the Bruins in goal, Brian Glennie from the Leafs on defence, and forwards Stan Mikita of the Hawks and Dale Tallon of the Canucks.  Team Canada celebrates following a goal against the Soviet Union during Game 2 action of the 1972 Summit Series at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto on September 4, 1972. (Photo by Robert Shaver/Hockey Hall of Fame) A pair of Toronto Maple Leafs executives scouted the Soviet team and reported that the Canadians would win handily. Almost all predictions for the series heavily favoured Team Canada. It seemed difficult to comprehend that that the Soviet team could be a match for the best players of the National Hockey League. The Canadian team took the series lightly - a serious mistake that they would soon regret. The first game, played September 2, 1972 in Montreal, saw the Canadians leap out to a 2-0 lead in the first period, but that confidence was quickly erased as the Soviets roared back to a dominating 7-3 final score. "The myth of unbeatable Canadian pros is over," declared Soviet broadcaster Nikolay Ozerov. "They completely underestimated us at the beginning," stated Soviet winger Alexander Yakushev.  Jersey worn by Canada's Rod Seiling during the 1972 Summit Series against the Soviet Union. Jersey worn by Canada's Rod Seiling during the 1972 Summit Series against the Soviet Union. (Photo by Matthew Manor/Hockey Hall of Fame) The Soviets arrived in Canada well prepared for the series. Their conditioning was very good, unlike the Canadians. "We hadn't trained very much or very hard," remembers Phil Esposito. "We ran out of gas." In the dressing room after that first game, Harry Sinden just shook his head as he addressed the team. "Gentlemen," he began. "We are in for a long, tough series. And we better get our act together." Game Two was played in Toronto on September 4, and the Canadians rebounded with a 4-1 win. But the third game, a contest played September 6 in Winnipeg, ended in a 4-4 draw. And then, the final game on Canadian soil -- September 8 in Vancouver.  Alexander Maltsev of the Soviet Union skates with the puck while Canada's Pat Stapleton defends during 1972 Summit Series game action at Luzhniki Ice Palace in Moscow. Alexander Maltsev of the Soviet Union skates with the puck while Canada's Pat Stapleton defends during 1972 Summit Series game action at Luzhniki Ice Palace in Moscow. (Photo by NDE/Hockey Hall of Fame) The Soviet squad completely dominated Team Canada, and the game ended in a 5-3 win for the USSR. The fans booed Team Canada off the ice. Phil Esposito addressed the hockey nation in a televised post-game interview: "People across Canada, we tried. We gave it our best but they've got a good team. And we don't know what we can do better, but we are going to figure it out." It was a pivotal moment in the series. "I gave the whole country a tongue-lashing on national television," Esposito wrote in his autobiography, Thunder and Lightning.  Gloves worn by Canada's Jean Ratelle during the 1972 Summit Series against the Soviet Union. Gloves worn by Canada's Jean Ratelle during the 1972 Summit Series against the Soviet Union. (Photo by Matthew Manor/Hockey Hall of Fame) The remainder of the series was to take place in Moscow. Team Canada had to do their homework if they were to come back to beat the Soviets. Besides conditioning, Canada had to gel as a team. The Soviets had played together for several months and, in some cases, several years while Team Canada was comprised of players from rival NHL teams, many of whom didn't particularly like each other. At this point, they had to play together against a very good opponent if they had any designs on winning the series. Harry Sinden made some difficult decisions. Having earlier told the entire team that they'd all get the opportunity to play, he was forced to change his tactic and pared the roster down to the players with whom he was confident that he could return to Canada with the series win. The frustration of not being selected boiled over, and a few players returned to the training camp of their NHL team. Team Canada bonded much better during two games played against the Swedish National Team between the first four games of the Summit Series and the final four. Most members agree that it was in Sweden where Team Canada really became a team. The Canadians, having been scolded by Phil Esposito, responded with enthusiasm. More than 3,000 fans travelled to Moscow to cheer on their team, and the Canadian players were welcomed with 10,000 telegrams of support upon their arrival on Soviet soil.  Canada and the Soviet Union get set to battle in Game 8 of the 1972 Summit Series at the Luzhniki Ice Palace in Moscow on September 28, 1972. Canada and the Soviet Union get set to battle in Game 8 of the 1972 Summit Series at the Luzhniki Ice Palace in Moscow on September 28, 1972. (Photo by John Wilson/Hockey Hall of Fame) On September 22, the series resumed with Game Five ending in a 5-4 victory for the Soviets. There were some very positive signs for the Canadians, though, including a 3-0 lead going into the third period and the igniting of a player named Paul Henderson, who tallied twice for Team Canada. Canada muscled through Game Six on September 24 with a 3-2 win, and Paul Henderson scoring the winning goal midway through the second period. He repeated that feat in Game Seven, scoring a magnificent goal by beating two Soviet defenders alone late in the third period to win the game 4-3 on September 26. "I call the Game Seven winner absolutely the best goal I ever scored in my life," Henderson states. Going into Game Eight on September 28, 1972, the series had the Soviet Union with three wins, Canada with three wins and one contest ending in a tie. The series came down to a single game, and it's one that has been glorified for four decades. After the first period, the Soviet Union and Canada were tied at two goals apiece, but after the second period, the USSR was up 5-3, yet, there was no panic on the Canadian side. "Despite the deficit, everyone in the dressing room was confident and upbeat," recalls Henderson. "The thought of losing didn't cross any of our minds."  Canada's Paul Henderson celebrates after scoring the 1972 Summit Series winning-goal against the Soviet Union in Game 8 at the Luzhniki Ice Palace in Moscow on September 28, 1972. Canada's Paul Henderson celebrates after scoring the 1972 Summit Series winning-goal against the Soviet Union in Game 8 at the Luzhniki Ice Palace in Moscow on September 28, 1972. (Frank Lennon) Canada scored two unanswered goals in the third to tie the score at 5-5. With less than a minute to play, Henderson, the hero of the two previous games, instigated a line change. "I stood up at the bench and called Pete Mahovlich off the ice. I'd never done such a thing before. I jumped on and rushed straight for their net. I had this strange feeling that I could score the winning goal. I had a great chance just before I scored, but (Yvan) Cournoyer's pass went behind me. Then, I was tripped up and crashed into the boards behind the net. I leaped up and moved in front, just in time to see (Phil) Esposito take a shot at Tretiak from inside the faceoff circle. The rebound came right to my stick and I tried to slide the puck past (Vladislav) Tretiak. He got a piece of it, but a second rebound came right to me. This time, I flipped the puck over him and into the net." "Henderson has scored for Canada!" exclaimed broadcaster Foster Hewitt. It was the shot 'heard 'round the world.' Canada held the Soviets off the scoresheet for the remaining 34 seconds to win the game...and the series. "If you'd been writing the script, it couldn't have produced a more dramatic and exciting final," declared Hewitt.  Helmet worn by Soviet Union forward Alexandre Yakushev during the eight games of the 1972 Summit Series against Canada. Helmet worn by Soviet Union forward Alexandre Yakushev during the eight games of the 1972 Summit Series against Canada. (Photo by Matthew Manor/Hockey Hall of Fame) "We were thrilled," recalls Ron Ellis. "In some ways, we couldn't believe that we'd done it. We went into the dressing room, but after a few high-fives and some whooping it up, we went to our seats and sat down. We were emotionally drained. It took us a couple of days before we could really celebrate and realize what we had accomplished." For Canadians, it was the greatest hockey victory in the history of the nation. The series has taken on mythical proportions. Paul Henderson's series-winning goal has become known as the 'Goal of the Century,' and was named one of the top ten events of the 20th century in Canadian history. An exhibition series between the finest the Soviet Union had to offer and the best Canada could provide concluded in a titanic struggle that changed the way hockey is played in North America. Although the political sensibilities of the Cold War prevented any of the Soviet players from joining the National Hockey League, NHL teams introduced elements of the Soviet style and conditioning into their programs. Eventually, with the fall of the Iron Curtain, elite Soviet players were able to join NHL teams. And the Summit Series paved the way for the best from each nation to participate in hockey events, including the Canada Cup and World Cup tournaments and later, Canadian professionals were finally allowed to play in International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) events, first at the World Championships and then, in the Winter Olympic Games. "I cherish the opportunity I had to be part of that team and represent Canada," concludes Ron Ellis. "We knew at the time that we were involved in a wonderful series, a unique series, but I don't think any of us expected (the Summit Series) to live as long as it has. I am so grateful that I was able to represent my country and our way of life in the Series of the Century." Kevin Shea is the Editor of Publications and Online Features for the Hockey Hall of Fame. Последний раз редактировалось Николай Озеров; 03.04.2016 в 15:08. |

|

#37

|

||||

|

||||

Summit Series: Nine members of great Soviet team no longer with us | Toronto Star |

|

#38

|

||||

|

||||

|

http://www.thestar.com/sports/hockey...ed_it_cox.html

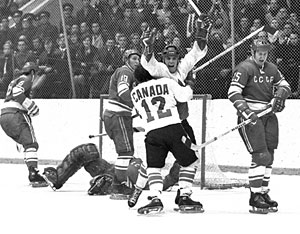

Series goal to have lived it: Cox Paul Henderson goal against Russia in 1972 Summit Series became part of Canada’s maturation into a nation Share on Facebook Reddit this! frank lennon shot of paul henderson..Yvon Cournoyer (12) of Team Canada hugging Paul Henderson after scoring the winning goal in the Canada U.S.S.R. hockey series in Sept. 28, 1972.  Frank Lennon / Toronto Star file photo frank lennon shot of paul henderson..Yvon Cournoyer (12) of Team Canada hugging Paul Henderson after scoring the winning goal in the Canada U.S.S.R. hockey series in Sept. 28, 1972. By: Damien Cox Sports Columnist, Published on Fri Sep 21 2012 There’s this sorting out process that accompanies aging, a sorting out of the memories that matter and the memories that must have because you were there and everyone says something big happened. From here, from this point in my life, I can’t tell you with any honesty I know where I was when Paul Henderson scored. Might have been in a classroom at Norwood Park School on Hamilton Mountain because there’s definitely a memory of a TV being wheeled in to Mrs. Howard’s Grade 7 class and a game, not sure which game, being beamed in from Moscow. Then again, I might have been in the park near my house, throwing a ball, because there’s also a memory of not being in school, being let out early because Team Canada was playing, and what 11-year-old was going to go inside to watch a grainy hockey image in his living room when it was September and sunny and we weren’t in school? So did I see it? Do I remember it? Mine wasn’t a hockey family. I wasn’t playing hockey yet, and none of my siblings were. My parents were English immigrants, and there certainly wasn’t a gathering at the dining room table at 488 Upper James where Mum and Dad explained why this mattered so much. When it came to the Soviets and their intentions, I remember much more clearly Dad telling me in 1979 when the U.S.S.R. rolled into Afghanistan that they’d never, ever leave. Most other stuff he got right. And I can’t say I ever remember any of my three brothers or two sisters EVER talking about Henderson’s goal. Maybe they did. But this notion that every Canadian family lived and died with every moment, every shot and every goal, of that ’72 Summit Series is, I think, somewhat exaggerated with time. But I remember something. I remember a time, and a sense of something happening, and a sense for the first time that sports were connected to something beyond the games. The Munich Olympic massacre had just happened three weeks earlier, which made no sense at all to this dopey kid but was obviously very bad. Later that fall Ian Sunter kicked the Grey Cup-winning field goal down at Ivor Wynne, and that mattered a lot because Dave Spisak’s dad took me to the odd game and his lucky family lived a few houses away from Dave Fleming, the Tiger-Cat scatback. That gave me a connection to an important event in sport. The next year, Secretariat would rule the horse-racing world and for some reason I watched every race, probably more races than I’ve watched since. It seemed important, and piled on top of Munich and Sunter and, of course, Bobby Orr’s Stanley Cup winner that I’m pretty sure I watched next door at the Reilly’s, together this was a bundle of significant sporting events that seemed to tell me sports had an importance, that they didn’t matter necessarily but really mattered to many. Otherwise, I only knew what Bob Hanley opined on in the Hamilton Spectator and that everyone wanted to be Dave Keon in road hockey and that Bill Spunska was a Scrub on Skates and that I loved hockey cards without the slightest suggestion they were valuable. Somewhere in that jumble of memories and events and half-formed ideas lived Henderson’s goal. It meant “we” had won, and we meant us and the Soviets were surely “them” and, with all the military officers and grim faces, not a “them” I could imagine being anything like us. More people, it seems to me, had seen the series opener in Montreal, and been shocked by an ugly result. There was no Bobby Hull or Orr, and Frank Mahovlich was a huge name but it was his brother, Pete, who scored the memorable solo goal in Game 2 at Maple Leaf Gardens. Ken Dryden and Tony Esposito, so dominant in the NHL, suddenly seemed very vulnerable when the Soviets were shooting. That was weird, made no sense. So I watched much of the competition, for sure. For most of the series it seemed we would lose because those Soviets always seemed to have the puck. People with opinions that mattered seemed to think this would be a terrible thing, and the good versus evil element is always easily sold, particularly when you’re the good. So then the goal happened and saved the day for Canada, for an 11-year-old’s burgeoning sense of Canada. My dad and his dad had gone to Expo 67 and we sang “O Canada” and “God Save the Queen” every day in school. So while I didn’t think of Canada as a young nation still finding itself, a nation that would surely feel the imprint of an event like Henderson’s goal, that’s what Canada was and I was part of it, really without actually knowing it. So did I actually see the Henderson goal when it happened? Or have I just seen it so many times since that it reinforces a memory that wasn’t really there in the first place? I’m just not sure. Maybe, maybe not. But I didn’t have to see it. I have lived it. Then, and ever since. That goal, whether I saw it or not, is part of me. And always will be. MORE: Canada’s Hat Trick 1987 Canada Cup: Gretzky to Lemieux at 1987 Canada Cup one of finest goals in nation’s history: Kelly 2012 Vancouver Olympics: Sidney Crosby’s golden goal the biggest in a generation |

|

#39

|

||||

|

||||

|

https://www.nhl.com/news/1972-summit...ockey/c-640724

by John Kreiser / NHL.com September 1st, 2012 Forty years ago Sunday, the hockey world was fundamentally changed by the start of an eight-game series between national teams from Canada, loaded with NHL players in their prime, and the Soviet Union -- considered the two best hockey-playing nations in the world at the time -- that played out across the month of September. The series was a must-follow for hockey fans across the globe and after its dramatic conclusion --- a 4-3-1 series win for the Canadians -- there was no question that the NHL would never be the same again. This month, NHL.com looks at the historic Summit Series with a month-long collection of content. Today, NHL.com provides an overview of what the series meant from some of those who helped make the history happen. Stay tuned for additional comment throughout September. Has it really been 40 years? The first weekend of September 1972 was marked by the start of the greatest hockey series ever staged. It's become known as the Summit Series, though four decades ago it was simply called the Canada-U.S.S.R. series – an eight-game showdown between hockey’s two superpowers. ANNIVERSARY OF 1972 SUMMIT SERIES  Forty years have passed since Canada and the Soviet Union met in a landmark eight-game series that changed hockey forever, and the effects are still evident in the sport all these years later. NHL.com now turns back the clock to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the 1972 Summit Series. Sunday, Sept. 2: Game 1 recap Tuesday, Sept. 4: Game 2 recap Thursday, Sept. 6: Game 3 recap Saturday, Sept. 8: Game 4 recap Saturday, Sept. 22: Game 5 recap Monday, Sept. 24: Game 6 recap Wednesday, Sept. 26: Game 7 recap Friday, Sept. 28: Game 8 recap On Sept. 2, 1972, Team Canada – basically the best of the National Hockey League minus Bobby Hull, who had signed with the fledgling World Hockey Association and was deemed ineligible to play, and injured superstar Bobby Orr – began a long-awaited series against the Soviet Union's national team, which was the best "amateur" team of the time. This was an era when professional players were ineligible for the Olympics; the Soviet players ostensibly held jobs (many were in the military), but their real occupation was "hockey player." The NHL was not the 30-team, coast-to-coast enterprise we know today. There were 14 teams -- only three in Canada and just two (Vancouver and Los Angeles) west of St. Louis, which was also the southernmost franchise except for L.A. With the exception of a small sprinkling of Americans, it was a league of Canadians that was sure it played the best hockey in the world. The Soviets were a mystery. They had won the prior three Olympic gold medals after being upset by the United States at Squaw Valley in 1960, but Canada had to use amateurs -- and for the 1972 Games, the Canadians didn’t even bother sending a team because of a dispute with the International Ice Hockey Federation. Canadian fans felt that had their country been able to send its best players, the result would have been a lot different. Scouting back then was nowhere near as developed as it is now, and none of the Canadian players had seen much of the Soviets. "We didn't know anything about them," Hall of Fame member Rod Gilbert told NHL.com. "We had no idea how good they were." After negotiations that involved Canadian diplomats and Soviet newspaper editors, among others, the series was set for September 1972, prior to the start of the new NHL season. The format was simple – eight games, four in each country, to see which nation really had the best hockey. Seeing Russians in the NHL is something we take for granted today -- many have been among the League’s best players in the two decades since the end of the Iron Curtain. But this was 1972; the series would be played at the height of the Cold War and provoked intense feelings of nationalism among fans on both sides. "There was great pressure on us," Gilbert said. "We couldn't lose this series. It was the most incredible pressure I've ever been under." Still, Canadian fans were certain that the best of the NHL would make short work of the Soviets; in a pre-tournament poll of Canadian journalists by The Hockey News, not one expected the Soviets to win even one game -- though some others, who had seen the Soviets in person, warned that they would arrive in top shape and could well win not only a game or two but the series. "Both teams won in 1972. It was a great series for all of hockey. The best that Russia had and the best of the NHL. The winner was the game of hockey." -- Vladislav Tretiak, president of the Russian Ice Hockey Federation "We didn't take them seriously," said forward Paul Henderson, who went on to be the hero of the series. "We knew they were good hockey players. But the lineup we had -- how could we ever lose?" They got a quick answer when the Soviets overcame an early 2-0 deficit to win the first game 7-3 in Montreal. The Soviets were 3-1-1 before Team Canada rallied to win the final three games in Moscow, capturing the series when Henderson's last-minute goal gave the Canadians a 6-5 victory in the eighth and final game on Sept 28. Henderson’s goal set off celebrations all over Canada, which less than a month earlier was certain its heroes were headed for an eight-game sweep. The series, and especially Henderson's third winner in as many games, became a landmark cultural event in Canadian history and a huge source of national pride. But it also showed that the Soviets' "amateurs" were just as good as the NHL’s professionals, something they proved numerous times before the walls between pros and amateurs came tumbling down along with the Iron Curtain. But the biggest consequence of the series was what Soviet star Boris Mikhailov called "a meeting between two schools of hockey." The fruits of that meeting, and the changes it engendered in the sport, are still felt today. "Both teams won in 1972," Vladislav Tretiak, now the president of the Russian Ice Hockey Federation, told TSN this summer. "It was a great series for all of hockey. The best that Russia had and the best of the NHL. The winner was the game of hockey." |

|

#40

|

||||

|

||||

|

http://www.cbc.ca/sports-content/hoc...le-ending.html

By Gord Stellick Posted: Thursday, September 27, 2012 | 06:43 PM Back to accessibility links  Paul Henderson, while on the ground, drives the puck past the Soviet Union's goalie Vladislav Tretiak in Game 7 for the second of his game-winning goals in the 1972 Summit Series. (CP Archive) Paul Henderson, while on the ground, drives the puck past the Soviet Union's goalie Vladislav Tretiak in Game 7 for the second of his game-winning goals in the 1972 Summit Series. (CP Archive) Supporting Story Content The script that had gone so horrible awry for Team Canada's hockey fans was about to have an ending that no script writer could have written, as it would have been deemed unbelievable. After being down 1-3-1 in the first five games of the Summit Series, Team Canada had faced the daunting and seemingly impossible task of needing to win three consecutive games on Soviet soil in order to win the Summit Series, a series that most Canadian fans had considered a sure thing when it was announced. A series that forever remained in doubt, and at times serious doubt, after that 7-3 drubbing in Game 1 in Montreal. Team Canada had eked out another hard fought one goal victory, 4-3, over the Soviet Union in Game 7. Paul Henderson scored the game winner in spectacular style with 2:06 left in the game. Henderson called it "one of the greatest moments of his life." Little did he know that it would pale by comparison for what was in store. Game 7 had introduced a new element of ugliness that had permeated the series. In the third period the TV cameras clearly caught Boris Mikhailov kick defensive standout Gary Bergman with his skate. Twice! Bergman's reaction to what he considered the unthinkable was priceless. He looked like a bull enduring the pain of being branded as he turned to scuffle with the Soviet player. While there was some talk of the Mikhailov kick, there was little or no talk of the Bobby Clarke slash that had ended the Summit Series for Soviet standout Valery Kharlamov. Since the rough play, physical play and dirty play had been a staple of this series, Team Canada was initially pleased with the officiating assignment for Game 8. After Game 6, it was announced that the two German officials that Team Canada despised, Franz Baader and Josef Kompalla (nicknamed Baader and Worse by Team Canada players and officials) had been "sent home." Czech referee Rudy Bata and Swedish referee Ove Dahlberg had officiated Game 7, and were set for Game 8. So it was not well received by the Canadians when they learned there was to be a last minute change with the officiating. Bata was to be paired with the loathed Kompalla, who had been sending a steady stream of Team Canada players to the penalty box in earlier games. I can remember Foster Hewitt's opening to the game: "I wouldn't miss this game for all the tea in China." Might have been the first and last time I heard that phrase on a sports broadcast. A few hours later, when Paul Henderson's life would change for ever, Foster Hewitt would broadcast arguably his "greatest" call in his distinguished Hall of Fame career. September 28th, 1972. All of Canada came to a standstill. All were glued to their television sets in a manner never truly replicated. The unbelievable script would play out for an unbelievable ending! |

|

| Здесь присутствуют: 1 (пользователей: 0 , гостей: 1) | |

|

|